Petition by ladies in Steubenville, OH, against Indian removal

Original

Background Notes

One of the strategies developed to deal with the conflict between white American settlers and Native American lands was to negotiate treaties, which voluntarily exchanged the lands of Indian tribes in the east for lands west of the Mississippi. Five assimilated tribes, the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminoles, known as the "Five Civilized Tribes" negotiated approximately thirty treaties with the United States between 1789 and 1825. In 1824, President Monroe announced to Congress that he thought all Indians should be relocated west of the Mississippi. Monroe was pressured by the state of Georgia to make his statement because gold had been discovered on Cherokee land in Northwest Georgia and the state of Georgia wanted to claim it. The Cherokee's resisted and sought to maintain their land. They had adopted a formal constitution, declared an independent Cherokee nation, and elected John Ross as their Chief in 1828. As expected, the Georgia legislature annulled the Cherokee constitution and ordered seizure of their lands. The Cherokees again resisted and took their claim of sovereignty to the United States Supreme Court. In their second case, Worcester v. Georgia, (1832) Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Cherokee Nation was entitled to federal protection over those of the state laws of Georgia. The Court ruled "the Indian nation was a "distinct community in which the laws of Georgia can have no force" and into which Georgians could not enter without the permission of the Cherokees themselves or in conformity with treaties. An outraged President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the ruling. Instead, Jackson used the funding from his newly created Indian Removal Act of 1830 to forcibly remove the recalcitrant tribes. There were, however, small pockets of opposition to the removal of Cherokees in Georgia and occasionally groups of people, such as the Quakers and an occasional abolitionist championed their rights. These women from Steubenville, Ohio used their only political right, the right of petition, to protest the Cherokee removal and to argue in favor of Native American natural rights. Their petition was ignored.

Robert V. Hine and John Mack Faragher, The American West, A New Interpretive History ( New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 176; Mary Beth Norton et al, A People and a Nation; A History of the United States. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1986), 287-290.

Transcription of Primary Source

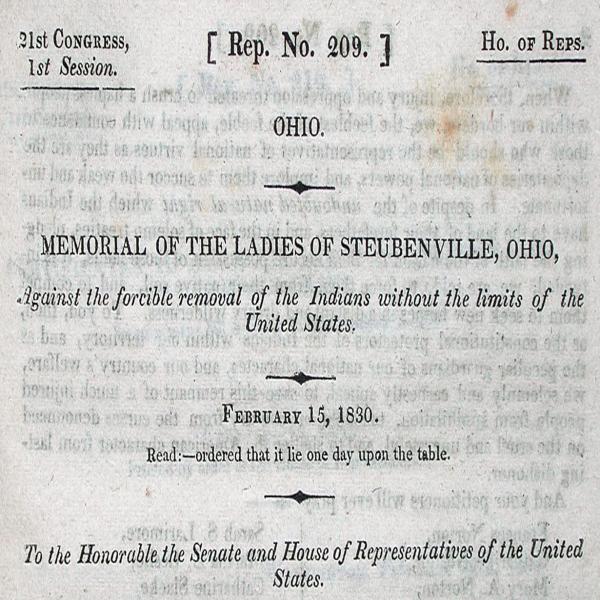

21st CONGRESS, [Rep. No. 209.] HO.OF REPS.

1st Session

MEMORIAL OF THE LADIES OF STEUBENVILLE, OHIO,

Against the Forcible removal of the Indians without the limits of the

United States

-

FEBRUARY 15, 1830

Read:- ordered that it lie upon the table.

-

To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States.

The memorial of the undersigned, residents of the state of Ohio, and town of Steubenville,

RESPECTFULLY SHEWETH:

That your memorialists are deeply impressed with the belief, that the present crisis in the affairs of the Indian nations, calls loudly on all who can feel for the woes of humanity, to solicit, with earnestness, your honorable body to bestow on this subject, involving, as it does, the prosperity and happiness of more than fifty thousand of our fellow Christians, the immediate consideration demanded by its interesting nature and pressing importance.

It is readily acknowledged, that the wise and venerated founders of our country's free institutions have committed the powers of Government to those whom nature and reason declare the best fitted to exercise them; and your memorialists would sincerely deprecate any presumptuous interference on the part of their own sex with the ordinary political affairs of the country, as wholly unbecoming the character of the American females. Even in private life, we may not presume to direct the general conduct, or control the acts of those who stand in the near and guardian relations of husbands and brothers; yet all admit that there are times when duty and affection call on us to advise and persuade, as well as to cheer or console. And if we approach the public Representatives of our husbands and brothers, only in the humble character of suppliants in the cause of mercy and humanity, may we not hope that even the small voice of female sympathy will be heard?

Compared with the estimate placed on woman, and the attention paid to her on other nations, the generous and defined deference shown by all ranks and classes of men, in this country, to our sex, forms a striking contrast; and as an honorable and distinguishing trait in the American Character, has often excited the admiration of intelligent foreigners. Nor is this general kindness lightly regarded or coldly appreciated; but, with warm feelings of affection and pride, and hearts swelling with gratitude, the mothers and daughters of America bear testimony to the generous nature of their countrymen.

When, therefore, injury and oppression threaten to crush a hapless people within our borders, we, the feeblest of the feeble, appeal with confidence to those who should be representatives of national virtues as they are the depositaries of national powers, and implore them to succor the weak and unfortunate. In despite of the undoubted national right which the Indians have to the land of their forefathers, and in the face of solemn treaties, pledging the faith of the nation for their secure possession of those lands, it is intended, we are told, to force them from their native soil, to compel them to seek new homes in a distant and dreary wilderness. To you, then, as the constitutional protectors of the Indians within our territory, and as the peculiar guardians of our national character, and our counter's welfare, we solemnly and honestly appeal, to save this remnant of a much injured people from annihilation, to shield our country from the curses denounced on the cruel and ungrateful, and to shelter the American character from lasting dishonor.

And your petitioners will ever pray.

Frances Norton,

Catharine Norton,

Mary A. Norton,

M. J. Hodge,

Emily N. Page

Rachel Mason,

E. Anderson,

S. Ashburn

A.Wilson,

S. J. Walker,

E. J. Porter,

A.Cushener,

M. J. Kelly,

Frances P. Wilson,

Eliza M. Rogers,

Ann Eliza Wilson,

Sarah Moodey,

Mary Jenkinson,

Jane Wilson,

Editha Veirs,

Mary Veirs,

Nancy Fuston,

Sarah Hoghland,

Nancy Laremore,

Nancy Wilson,

Elizabeth Sheppard,

Mary C. Green,

Anna Woods,

Anna Dike,

Margaretta Woods,

Margaret Larimore,

Maria E. Larimore,

Sarah S. Larimore,

Martha E. Leslie,

Catharine Slacke,

W. D. Andrews,

P. Lord,

Eliza S. Wilson,

Sarah Wells,

Rebecca R. Morse,

Hetty E. Beatty,

Caroline S. Craig,

Elizabeth Steenrod,

Elloisa Lefflen,

Lucy Whipple,

N. Kilgore,

C. Colwell,

E. Brown,

M. Patterson,

R. Craig,

J. M. Millan,

Betsey Tappan,

Margaret M. Andrews,

Sarah Spencer,

Mary Buchannan, do.,

Rebecca J. Buchannan, do.,

Hetty Collier,

Eunice Collier,

Elizabeth Beatty,

Jane Beatty,

Sarah Means,

Elizabeth Sage.