Approaches

Why did Douglas introduce the Kansas-Nebraska bill?

Given its disastrous consequences, the question of what Douglas hoped to achieve with the measure is an obvious starting place. In a letter, Douglas gave this explanation:

How are we to develop, cherish and protect our immense interests and possessions in the Pacific, with a vast wilderness fifteen hundred miles in breadth filled with hostile savages, and cutting off direct communication? The Indian barrier must be removed. The tide of emigration and civilization must be permitted to roll onward until it rushes through the passes of the mountains, and spreads over the plains, and mingles with the waters of the Pacific. Continuous lines of settlements with civil, political and religious institutions, under the protection of law, are imperiously demanded by the highest national considerations. These are essential, but they are not sufficient. . . . We must therefore have Rail Roads and Telegraphs from the Atlantic to the Pacific, through our own territory. Not one line only, but many lines, for the valley of the Mississippi will require as many Rail Roads to the Pacific as to the Atlantic, and will not venture to limit the number.

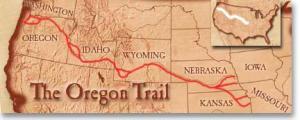

The United States's new "empire on the Pacific," as President Polk had referred to California in his diary, made the question of speeding up travel and communication imperative, not only in Douglas' opinion but in those of virtually all white Americans. There were three ways of getting to California and the Oregon Territory; all were time-consuming and expensive. One was by sea, through the Straits of Magellan and up the coast of South America. The voyage took many months, sometimes as long as a year. A second route was also by sea but involved cutting across Nicaragua, thereby greatly reducing the time required. But travelers could still expect the journey to take months. The third was the Oregon Trail. [Click on the map for a link to The Oregon Trail, a site for teachers created by the authors of the PBS series on the trail.] This was the way west for the pioneers Douglas was so eager to encourage. They could not afford the ocean travel. And many lived hundreds of miles inland. Their 2,000 mile journey would also take months to complete.

The United States's new "empire on the Pacific," as President Polk had referred to California in his diary, made the question of speeding up travel and communication imperative, not only in Douglas' opinion but in those of virtually all white Americans. There were three ways of getting to California and the Oregon Territory; all were time-consuming and expensive. One was by sea, through the Straits of Magellan and up the coast of South America. The voyage took many months, sometimes as long as a year. A second route was also by sea but involved cutting across Nicaragua, thereby greatly reducing the time required. But travelers could still expect the journey to take months. The third was the Oregon Trail. [Click on the map for a link to The Oregon Trail, a site for teachers created by the authors of the PBS series on the trail.] This was the way west for the pioneers Douglas was so eager to encourage. They could not afford the ocean travel. And many lived hundreds of miles inland. Their 2,000 mile journey would also take months to complete.

Douglas placed more emphasis upon the "Indian barrier," the "vast wilderness fifteen hundred miles in breadth filled with hostile savages" than on the need to make the trip to the West faster. They had to be "removed." Opening the unorganized territories to settlement would sweep the "savages" aside. So an important element in Douglas' thinking was Indian Removal, a continuation of the process examined in the section on The Trail of Tears on this site.

Douglas wanted "many" railroad lines. But building the first would be an enormous task, one that would require immense federal subsidies, and one that would as profoundly shape the development of the Midwest as it would that of the West. The map, from the Library of Congress American Memory teaching site on railroad maps, as modified, shows the transcontinental routes under consideration when Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska bill.

The choice quickly boiled down to two northern and two southern routes. Either northern route would make Chicago the eastern terminus, either southern route St. Louis. And the two senators who had the most to do with the passage of Kansas-Nebraska were Stephen Douglas of Illinois and David Atchison of Missouri. Some historians, notably David Potter, argue that Douglas offered to repeal the Missouri Compromise and open Kansas, due west of Missouri, to slavery to gain Atchinson's support for a northern route. If that was his motivation, it failed. Atchison supported Kansas-Nebraska, and then personally led "Missouri Ruffians" into the territory to vote and to overthrow the free soil territorial government, but he continued to support the southern route that would make St. Louis the rail hub of the Midwest.

There were other factors beyond a desire to rid the West of native peoples, connect the Pacific to the rest of the country, and boom either Chicago or St. Louis for organizing the Nebraska territory. As the Emigrant Aid Society, founded to encourage free soilers and immigrants to settle Kansas, pointed out in its first Report:

. . . all accounts agree that the region of Kansas is the most desirable part of America now open to the emigrant. It is accessible in four days of continuous travel from Boston. Its crops are very bountiful, its soil being well adapted to the staples of Virginia and Kentucky and especially to the growing of hemp. In its eastern section, the woodland and prairie-land intermix in proportions very well adapted for the purposes of the settler. Its mineral resources, especially its coal, in the central and Western parts, are inexhaustible. A steamboat is already plying on the Kansas River, and the Territory has uninterrupted steamboat communication with New Orleans, and all the tributaries of the Mississippi river. All the overland emigration to California and Oregon, by any of the easier routes, passes of necessity through its limits. Whatever roads are built westward must of necessity begin in its territory. For it is here that the emigrant leaves the Missouri River. Of late years the demand for provisions and breadstuffs made by emigrants proceeding to California, has given to the inhabitants of the neighboring parts of Missouri a market as at good rates as they could have found in the Union.

It is impossible that such a region should not fill up rapidly.

It was politically unthinkable that the territory not be opened to settlement. But, as soon as it was, the question of slavery in the territories would arise. The Compromise of 1850 had dealt with the territories acquired from Mexico. It admitted California as a free state, even though part of it lay below the Missouri Compromise line. It applied the principle of Popular Sovereignty to the Utah Territory, although part of it lay above the line. Did this mean that the line had been repealed in 1850? Or did it still apply to the territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase such as Kansas and Nebraska? Douglas (pictured at right) had finessed the question in 1850 but would have to confront it in 1854. Popular Sovereignty had defused the issue before. Douglas apparently hoped it would work a second time.

It was politically unthinkable that the territory not be opened to settlement. But, as soon as it was, the question of slavery in the territories would arise. The Compromise of 1850 had dealt with the territories acquired from Mexico. It admitted California as a free state, even though part of it lay below the Missouri Compromise line. It applied the principle of Popular Sovereignty to the Utah Territory, although part of it lay above the line. Did this mean that the line had been repealed in 1850? Or did it still apply to the territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase such as Kansas and Nebraska? Douglas (pictured at right) had finessed the question in 1850 but would have to confront it in 1854. Popular Sovereignty had defused the issue before. Douglas apparently hoped it would work a second time.

Did he have an alternative? Yes. He could have filed a bill opening the territory under the terms of the Missouri Compromise. As Lincoln and others pointed out, the compromise line was a quid pro quo. It was what the South gave in return for the admission of Missouri as a slave state. A deal, Lincoln argued, was a deal. The South had already agreed that all the Louisana Purchase land north of the line would be forever closed to slavery. But Douglas was seeking to do more than open the territory to settlement. He was seeking southern support for his presidential ambitions. Some historians seize upon this factor to argue that it was Douglas' desire for higher office that led him to support repeal of the Compromise line. Alternatively, some argue that Douglas saw his bill as a way of benefiting the country and his home state and his own career. Such scholars point out that Douglas did not think that Kansas would become a slave state.

Reactions to the Kansas-Nebraska Act

Douglas did not anticipate the firestorm of criticism his bill provoked in the North or the intense support it gained in the South. He later joked that the outcry in the North was so intense that he could have traveled from Washington back to Chicago by the light of his own burning effigies. He was taken by surprise because he thought that both Kansas and Nebraska would necessarily become free states. His logic, which he repeated over and again, was that no slaveholder would bring his property into a new territory until there were sufficient legal protections for it. But, since no slaveholders would emigrate into Kansas, the necessary laws would not be passed. That would mean that slavery would never gain a foothold there. Lincoln dismissed this as a "lullaby argument" in his October 1854 speech in Peoria that launched his national political career:

In spite of the Ordinance of `87 [the Northwest Ordinance], a few negroes were brought into Illinois, and held in a state of quasi-slavery; not enough, however to carry a vote of the people in favor of the institution when they came to form a constitution. But in the adjoining Missouri country, where there was no ordinance of `87--was no restriction--they were carried ten times, nay a hundred times, as fast, and actually made a slave State. This is fact--naked fact.

The Albany, New York, Evening Journal [Whig] (23 May 1854) [From the Secession Era Editorials Project, Furman University] expressed some of the outrage in the North:

The crime is committed. The work of Monroe, and Madison, and Jefferson, is undone. The wall they erected to guard the domain of Liberty, is flung down by the hands of an American Congress, and Slavery crawls, like a slimy reptile over the ruins, to defile a second eden.

They tell us that the North will not submit. We hope it will not. But we have seen this same North crouch lower and lower each year under the whip of the slave driver, until it is hard to tell what it will not submit to now. Who, seven years ago, would not have derided a prophecy that Congress could enact the kidnapping of free citizens, without judge or jury? Who would have believed that it could enact that white men have a right to hold black in slavery wherever it is their sovereign will and pleasure? And yet, who now will deny that that prophecy is more than realized?

It was fitting that the Law should be passed as it was. It was in accordance with its spirit that it should be conceived in treachery, sprung upon the House by a fraud, and forced through it by a Parliamentary lie. It was appropriate that one member should be bribed and another bullied, and another bought, until the ranks of Slavery were full. Had Law or Order or Honesty had aught to do with its passage, there would have been a strange incongruity between the means and the end.

We cannot read the future. We cannot predict what will be the consequences of this last and most fatal blow to Liberty. But we can see what the duty of Freemen is, and we mean it shall be through no fault of ours if it is left undone.

The Jackson, Mississippi, Mississippian [Democratic] (31 March 1854) [From the Secession Era Editorials Project, Furman University] typified the militant southern reaction:

The contrast between the attitude of the opposers of the Nebraska Bill at the North, and its advocates at the South, is very striking, and affords much food for agreeable reflection to those who feel a just pride in the sound sense, and the calm, deliberate judgment which characterize the action of the people of the slave-holding States, upon questions of public interest.

Look to the North, and what do we realize? We are regaled by the coarse vituperation of the New York Tribune, and the insane ranting of Fessenden, (who was once appropriately toasted at a free negro festival as a "white brudder with a black heart,") the sickly cant of Sumner, -- the detestable demagogism of Seward, -- the horrid screeching of Lucy Stone, and her unsexed compatriots, -- the sacrilegious imprecations of ministers who degrade the holy calling, and the disgraceful orgies of tumultuous assemblages of all ages, colors, and conditions, who make night hideous with their frantic howlings. In the South, scarce a ripple seems to agitate the surface of society. All is calmness and equanimity. Here and there we read of resolutions adopted by Conventions of the people, or their legislature, but they are distinguished by no mark of intemperance and unnecessary excitement. We hear of no burnings in effigy, -- we witness no wild demonstrations; we listen to no furious declamation, -- we have no fanatical women roving over the country and bringing reproach upon the community in which they live, by mingling in affairs which pertain to the sterner sex, we have no preachers who convert the sacred desk into an arena of sectional strife, and whose blasphemies make the very angels weep.

A paper before us, says, that Isaac Toucey, a Connecticut Senator, who advocated the bill, has been hung in effigy, by a portion of his constituents. On his heart was a broad label, bearing the words, "Toucey, the traitor." It further remarks, that for thus betraying the "cause of freedom and his constituents" he deserved a "still more stinging rebuke." A public meeting at Leesburg, Ohio, resolves that "such member of Congress who votes for, or in any way gives countenance to, the bill for the organization of the Nebraska Territory, as reported by Senator Douglas, of Illinois, is a traitor to his country, to freedom and to God, worthy only of everlasting infamy." A remonstrance against the bill, signed by more than three thousand Clergymen of New England, characterizes it as a "great moral wrong," a "breach of faith," -- a measure full of danger to the peace and even existence of the Union, and exposing us to the righteous judgment of the Almighty. A newspaper which is everywhere regarded as the most influential organ of those who oppose the bill [New York Tribune], asks, "If the slave power, aided by a few deserters from freedom, intend to deliberately crowd and plunder the North as they propose in this Nebraska bill, how long can this government go harmoniously on?" A meeting at Amsterdam, New York, Resolves, "That the territory of Nebraska and Kansas is the sworn heritage of freedom -- That it shall never be reduced to slavery. That if by the degradation and treachery of demagogues, whom the North has honored to her own shame, freedom may be wounded in the house of her friends, we shall hold it to be our solemn duty, God helping us, through whatever peril the path may lie, to aid in restoring to the North and to humanity, all the rights and immunities of which they shall have been, through such degradation and treachery, deprived."

The Secession Era Editorials Project contains about one hundred editorials on Kansas-Nebraska. There are brief summaries of the positions taken in each. One way to get students to work with such a rich collection is to break them into teams by region and politics, i.e., northern Whigs, northern Democrats, southern Whigs, and southern Democrats. Alternatively, one can work on a few editorials intensively. What are the "hot button" terms in the two editorials quoted above? Students will quickly list "crime," "slimy reptile," "the whip of the slave driver," and other terms from the first and come up with an even longer list for the second, some of which will be quotations from northern editorials. What image of the South emerges in northern terminology? What image of the North in southern?

Territorial Elections, Border Ruffians, and the Collapse of the Rule of Law

This is a highly dramatic story and a very richly documented one. What follows is a brief narrative of the bloodshed in Bleedin' Kansas, with the omission of John Brown's Pottawatomie Creek Massacre, which gets its own section. There are links to the complete texts that are excerpted here.

In November of 1854, the first territorial election to select a delegate to Congress took place. Of 2871 votes cast, the Congressional Committee created in 1856 to investigate the Kansas "troubles" (the Howard Committee) determined that 1729 (60%) were illegal:

Thus your committee find that in this, the first election in the territory, a very large majority of the votes were cast by citizens of the State of Missouri, in violation of the organic law of the territory. Of the legal votes cast, Gen. Whitfield received a plurality. The settlers took but little interest in the election, not one-half of them voting. This may be accounted for from the fact that the settlements were scattered over a great extent, that the term of the [Congressional] delegate to be elected was short, and that the question of free and slave institutions was not generally regarded by them as distinctly at issue. Under these circumstances, a systematic invasion, from an adjoining state, by which large numbers of illegal votes were cast in remote and sparse settlements for the avowed purpose of extending slavery into the territory, even though it did not change the result of the election, was a crime of great magnitude. Its immediate effect was to further excite the people of the northern states, induce acts of retaliation, and exasperate the actual settlers against their neighbors in Missouri.

On March 30, 1855 there was another election, this one for a territorial legislature. There were, according the census just taken, 8,601 residents in Kansus, 2,905 of whom were eligible to vote. The Missourians returned in force. Acording to the Howard Committee, the special Congressional Committee,

The evening before, and the morning of the day of the election, about one thousand men arrived at Lawrence, and camped in a ravine a short distance from the town, and near the place of voting. They came, in wagons (of which there were over one hundred) or on horseback, under the command of Colonel Samuel Young, of Boone county, Missouri, and Claiborne F. Jackson, of Missouri. They were armed with guns, rifles, pistols and bowie knives; and had tents, music and flags with them. They brought with them two pieces of artillery, loaded with musket balls.

. . . . .

When the voting commenced, . . . Colonel Young offered to vote. He refused to take the oath prescribed by the governor, but said he was a resident of the territory. He told Mr. Abbott, one of the judges, when asked if he intended to make Kansas his future home, that it was none of his business; if he were a resident then he should ask no more. After his vote was received, Colonel Young got upon the window sill and announced to the crowd that he had been permitted to vote, and they could all come up and vote. He told the judges that there was no use swearing the others, as they would all swear as he had. After the other judges had concluded to receive Colonel Young's vote, Mr. Abbott resigned as judge of election, and Mr. Benjamin was elected in his place.The polls were so much crowded till late in the evening that for a time they were obliged to get out by being hoisted up on the roof of the building, where the election was being held, and passing out over the house. Afterwards a passageway was made through the crowd by two lines of men being formed, through which voters could get to the polls. Colonel Young asked that the old men be allowed to go up first and vote, as they were tired with the traveling, and wanted to get back to camp. During the day the Missourians drove off the ground some of the citizens, Mr. Stearns, Mr. Bond and Mr. Willis. They threatened to shoot Mr. Bond, and made a rush after him, threatening him. As he ran from them, shots were fired at him as he jumped off the bank of the river and escaped.

The pro-slavery forces triumphed as 6,307 men voted, a substantial number of them Missourians. Even if all 2,905 eligible voters had cast ballots, an unrealistic assumption, at least 3,402 others must have voted illegally. If the first election was "a crime of great magnitude," the second was more grievous still. This new territorial legislature would write the initial laws concerning slavery. They were the FEW Lincoln warned of who could bring slavery IN, thus thwarting the will of the MANY who wished to keep it OUT. Worse still, they had been elected by fraud.

Governor Andrew Reeder, appointed by President Pierce, accepted the election results, although he later changed his mind, repudiated them, and went over to the free state side. By then he had been removed from office by the administration. Before this happened, the legislature got down to business passing laws making the advocacy of anti-slavery sentiments a felony. They removed from office all appointees who would not declare in favor of slavery. They wrote a Slave Code more stringent than that in any of the slave states.

Free Soilers refused to acknowledge the new legislature. They were led by Dr. Charles Robinson, the agent of the Emigrant Aid Society. On July 4, 1855, he spoke to a free soil gathering:

I can say to Death, be thou my master, and to the Grave, be thou my prison house; but acknowledge such creatures as my masters, never! Thank God, we are yet free, and hurl defiance at those who would make us slaves.

Look who will in apathy, and stifle they who can,

The sympathy, the hopes, the words, that make man truly man.

Let those whose hearts are dungeoned up with interest or with ease,

Consent to hear, with quiet pulse, of loathsome deeds like these.

We first drew in New England's air, and from her hardy breast

Sucked in the tyrant-hating milk that will not let us rest.

And if our words seem treason to the dullard or the tame,

Tis but our native dialect; our fathers spake the same. [from James Russell Lowell, "On the Surrender of a Fugitive Slave"]Let every man stand in his place, and acquit himself like a man who knows his rights, and knowing, dares maintain. Let us repudiate all laws enacted by foreign legislative bodies, or dictated by Judge Lynch over the way. Tyrants are tyrants, and tyranny is tyranny, whether under the garb of law or in opposition to it. So thought and acted our ancestors, and so let us think and act. We are not alone in this contest. The whole nation is agitated upon the question of our rights. Every pulsation in Kansas pulsates to the remotest artery of the body politic, and I seem to hear the millions of freemen, and the millions of bondsmen in our own land, the patriots and philanthropists of all countries, the spirits of the revolutionary heroes, and the voice of God, all saying to the people of Kansas, "Do your duty."

Free soil partisans decided to declare the actions of the legislature invalid, to hold their own election, and to create their own territorial government with its own capital, Lawrence. A call went out to "all bona fide citizens of Kansas Territory, of whatever political views or predilections, to consult together, in their respective election districts," and elect "delegates to assemble in convention, at the town of Topeka, on the 19th day of September, 1855, then and there to consider and determine upon all subjects of public interest, and particularly upon that having reference to the speedy formation of a state constitution, with an intention of immediate application to be admitted as a state into the Union of the United States of America." A convention at Big Springs, on September 5, declared the Legislature elected in March was illegitimate and "that its laws had no validity or binding force; and that every freeman was at liberty, consistently with his obligations as a citizen and a man, to defy and resist them."

In early October first the pro-slavery and then the free soil partisans held elections for the Congressional delegate. Each boycotted the one called by the other. The free soilers also elected delegates to a Constitutional Convention, held later in the month in Topeka, which drafted a free state constitution that it submitted to the residents for ratification on December 15. It was approved, again with the pro-slavery side boycotting. They then set up an alternative territorial government with Dr. Charles Robinson serving as governor. It met in March 1856.

There were, as of that March, two territorial governments. One, recognized by the Pierce Administration, had stolen the March 1855 election and then had made the mere advocacy of anti-slavery a felony. The other had summoned itself into existence. It had not stolen the elections it sponsored. But proslavery settlers had boycotted them. So neither side could truthfully claim to represent the will of the people. Popular sovereignty had turned into anarchy.

Many historians, notably David Potter, have pointed out that "the great anomaly of 'Bleeding Kansas' is that the slavery issue reached a condition of intolerable tension and violence . . . in an area where a majority of the inhabitants apparently did not care very much one way or the other about slavery." An "overwhelming proportion of the settlers were far more concerned about land titles" than anything else. The explanation for this "anomaly" is not far to seek. Richard Cordley, a Congregational minister who came to the territory in 1857, wrote in his A HISTORY OF LAWRENCE, KANSAS: FROM THE EARLIEST SETTLEMENT TO THE CLOSE OF THE REBELLION, Published by E. F. Caldwell LAWRENCE, KANSAS 1895 LAWRENCE JOURNAL PRESS:

When the Kansas bill passed the people of the South expected to take possession of the territory. They urged those on the border to "move right over," and take their slaves with them. They said "two thousand slaves settled in Kansas would make it a slave state." But the southern people did not have the "courage of their convictions." They did not dare take their slaves over. There never were but a handful of slaves in Kansas, and these were on the border where they could be easily withdrawn. But southern people determined to take possession of Kansas, and as soon as the bill was passed the men in the border counties of Missouri began to rush over, and stake off claims. In a few weeks the whole region was claimed under the pre-emption laws by persons residing in Missouri. They paid no attention to the terms of the law, but each man marked off the land he wanted, drove a stake down and wrote his name upon it, and went back home. This gave them no title and no claim because it did not comply with the law. But they agreed among themselves to shoot any man who interfered with them. When the real settlers came two months later they found many embarrassments. They might travel fifty miles and not see a human habitation or a human face, but if they attempted to claim a piece of unoccupied land, they found it already claimed by somebody in Missouri. This man had not complied with the law, and had secured no title, but then he had a revolver and a bowie knife, and in the unwritten code of the border these stood for law and right, and pretty much everything else.

Under these conditions, settlers without connections to the proslavery side could expect no recognition of their claims. Pro-slavery settlers could count not only on the territorial government but also on various secret Missouri societies, all pledged to making Kansas a slave state. The Congressional Committee (the Howard Committee) offered this description. They were:

. . . known by different names, such as 'Social Band,' 'Friends' Society,' 'Blue Lodge,' 'The Sons of the South.' Its members were bound together by secret oaths, and they had passwords, signs and grips, by which they were known to each other. Penalties were imposed for violating the rules and secrets of the order. Written minutes were kept of the proceedings of the lodges, and the different lodges were connected together by an effective organization. It embraced great numbers of the citizens of Missouri, and was extended into other slave states and into the territory. Its avowed purpose was not only to extend slavery into Kansas, but also into other territory of the United States, and to form a union of all the friends of that institution. Its plan of operating was to organize and send men to vote at the elections in the territory, to collect money to pay their expenses, and, if necessary, to protect them in voting. It also proposed to induce pro-slavery men to emigrate into the territory, to aid and sustain them while there, and to elect none to office but those friendly to their views. This dangerous society was controlled by men who avowed their purpose to extend slavery into the territory at all hazards, and was altogether the most effective instrument in organizing the subsequent armed invasions and forays. In its lodges in Missouri the affairs of Kansas were discussed, the force necessary to control the election was divided into bands, and leaders selected, means were collected, and signs and badges were agreed upon. While the great body of the actual settlers of the territory were relying upon the rights secured to them by the organic law, and had formed no organization or combination whatever, even of a party character, this conspiracy against their rights was gathering strength in a neighboring state, and would have been sufficient at their first election to have overpowered them, if they had been united to a man.

John H. Gihon, M.D., secretary to Governor Geary, provided in GEARY AND KANSAS. GOVERNOR GEARY'S ADMINISTRATION IN K A N S A S: with a complete HISTORY OF THE TERRITORY U N T I L J U L Y 1857: EMBRACING A FULL ACCOUNT OF ITS DISCOVERY, GEOGRAPHY, SOIL, RIVERS, CLIMATE, PRODUCTS; ITS ORGANIZATION AS A TERRITORY, TRANSACTIONS AND EVENTS UNDER GOVERNORS REEDER AND SHANNON, POLITICAL DISSENSIONS, PERSONAL RENCOUNTRES, ELECTION FRAUDS, BATTLES AND OUTRAGES. ALL FULLY AUTHENTICATED. (1857) a vivid if hostile account of the Blue Lodges' early attempt to destroy the Lawrence settlement in 1854:

On the 6th of October a large body of armed men, in wagons and on horseback, with grotesque banners and other strange devices, came from Westport to Lawrence, to disperse the settlers at that place. They demanded that the abolitionists should take away their tents and be off at short notice, or otherwise they would be ''wiped out." The immigrants refused to obey this mandate, but prepared themselves in martial array, to protect their property and lives. This was entirely unexpected on the part of the invaders. They never imagined the possibility of the abolitionists showing fight. So, after considerable swaggering, they started back for Missouri, threatening, with huge oaths, that they would return in a week, with a force sufficiently large to compel submission to their requirements. These threats were unheeded; the settlers continued to build up their town; and the invaders did not return at the appointed time.

Bands of armed men were also organized to intercept the passage of the Missouri River. These parties entered the upward-bound steamboats at Lexington and other Missouri landings, and upon finding companies of northern emigrants, deprived them of their arms, and, in many instances, compelled them to go back. These outrages became so frequent and intolerant, that the river was virtually closed to all free-state travellers, who could only reach Kansas by taking the northern land route through lowa and Nebraska.

Gihon's account provided numerous examples of proslavery outrages, even though he insisted that the free state faction, especially Jim Lane's "Army of the North," committed almost as many. He quoted the Squatter Sovereign, a pro-slavery paper, version of what happened at Atchison:

"On Thursday last one Pardee Butler arrived in town with a view of starting for the East, probably for the purpose of getting a fresh supply of free-soilers from the penitentiaries and pest-holes of the northern states. Finding it inconvenient to depart before morning, he took lodgings at the hotel and proceeded to visit numerous portions of our town, everywhere avowing himself a free-soiler, and preaching the foulest of abolition heresies. He declared the recent action of our citizens in regard to J. W. B. Kelley [who was run out of town for his free state views], the infamous and unlawful proceedings of a mob; at the same time stating that many persons in Atchison, who were free-soilers at heart, had been intimidated thereby, and feared to avow their true sentiments; but that he (Butler) would express his views in defiance of the whole community.

"On the ensuing morning our townsmen assembled en masse, and, deeming the presence of such persons highly detrimental to the safety of our slave property, appointed a committee of two to wait on Mr. Butler and request his signature to the resolutions passed at the late pro-slavery meeting held in Atchison. After perusing the said resolutions, Mr. B. positively declined signing them, and was instantly arrested by the committee.

"After the various plans for his disposal had been considered, it was finally decided to place him on a raft composed of two logs firmly lashed together; that his baggage and a loaf of bread be given him; and having attached a flag to his primitive bark, emblazoned with mottoes indicative of our contempt for such characters, Mr. Butler was set adrift in the great Missouri, with the letter R legibly painted on his forehead.

"He was escorted some distance down the river by several of our citizens, who, seeing him pass several rock-heaps in quite a skilful manner, bade him adieu, and returned to Atchison.

"Such treatment may be expected by all scoundrels visiting our town for the purpose of interfering with our time-honored institutions, and the same punishment we will be happy to award all free-soilers, abolitionists, and their emissaries."

Butler claimed that Robert S. Kelley, the junior editor of the Squatter Sovereign was "one of the most active members of the mob that committed this disgraceful act, and that he assisted to tow the raft out into the stream, where he was set adrift, with flags bearing the following strange inscriptions: 'Eastern Emigrant Aid Express. The Rev. Mr. Butler for the Underground Railroad.' 'The way they are served in Kansas.' 'For Boston.' 'Cargo insured--unavoidable danger of the Missourians and the Missouri River excepted.' 'Let future emissaries from the north beware. Our hemp crop is sufficient to reward all such scoundrels.'"

Under such circumstances, non-slavery settlers had to turn to the Lawrence (free soil) side. They also made haste to arm themselves. As the Rev. Cordley told the story:

As soon as the result of the March election was finally determined, the free-state leaders sent to their friends in the east for arms. George W. Deitzler was sent to Boston to lay the matter before the friends of free Kansas. Only two persons knew of the object of his mission. New arms were needed for self-defense. Amos A. Lawrence [after whom Lawrence, Kansas was named and one of the backers of the free soil Emigrant Aid Society] and others, before whom Mr. Deitzler presented the case, at once saw the seriousness of the situation. Within an hour after his arrival in Boston, he had an order for one hundred Sharpe's rifles, and in forty-eight hours the rifles were on their way to Lawrence. They were shipped in boxes marked "books." As the border ruffians had no use for books, they came through without being disturbed. A military company known for many years afterwards as the "Stubbs" was organized, and was armed with these rifles. Other boxes of "books" rapidly followed these, and other companies in Lawrence and in the country were armed with them. The fame of these guns went far and wide, and produced a very salutatory effect. They who recognized only brute force came to have a great respect for the Sharpe's rifles. A howitzer was procured in New York through the aid of Horace Greeley, and shipped to Lawrence.

John Brown received his first public notice for transporting weapons for the free state side. The Herald of Freedom wrote:

About noon (December 7), Mr. John Brown, an aged gentleman from Essex County, N. Y., who has been a resident of the Territory for several months, arrived with four of his sons - leaving several others at home sick - bringing a quantity of arms with him, which were placed in his hands by Eastern friends for the defense of the cause of freedom. Having more than he could use to advantage, a portion of them were placed in the hands of those more destitute. A company was organized and the command given to Mr. Brown for the zeal he had exhibited in the cause of freedom both before and since his arrival in the Territory.

Neither Free Soilers nor their opponents were able to establish effective control over the territory. There were minor skirmishes, a great deal of threatening, innumerable disputes and arguments, but no real government. Neither side recognized the laws passed by the other; neither accepted the jurisdiction of the other's courts. And, despite all of the posturing, neither had taken the offensive. [Gihon provided a very detailed account of the "Wakarusa war" of December 1855, a move upon the free soil capitol of Lawrence which ended in a truce. John Brown was a participant in the "war" and described it at length in a letter to his family, reprinted in Cutler's History.] This standoff was about to change. On May 5, 1856 a grand jury returned an indictment which, as Gihon noted, amounted to a declaration of war upon the free soilers:

The grand jury, sitting for the adjourned term of the First District Court in and for the county of Douglas, in the Territory of Kansas, beg leave to report to the honorable court that, from evidence laid before them, showing that the newspaper known as The Herald of Freedom, published at the town of Lawrence, has from time to time issued publications of the most inflammatory and seditious character, denying the legality of the territorial authorities, addressing and commanding forcible resistance to the same, demoralizing the popular mind, and rendering life and property unsafe, even to the extent of advising assassination as a last resort;

Also, that the paper known as The Kansas Free State has been similarly engaged, and has recently reported the resolutions of a public meeting in Johnson county, in this territory, in which resistance to the territorial laws even unto blood has been agreed upon; and that we respectfully recommend their abatement as a nuisance. Also, that we are satisfied that the building known as the `Free-State Hotel' in Lawrence has been constructed with the view to military occupation and defence, regularly parapeted and port-holed for the use of cannon and small arms, and could only have been designed as a stronghold of resistance to law, thereby endangering the public safety, and encouraging rebellion and sedition in this country; and respectfully recommend that steps be taken whereby this nuisance may be removed. OWEN C. STEWART, Foreman.

The "steps" taken to remove "this nuisance" have come to be known as the "sack of Lawrence." I.B. Donaldson, the U.S. Marshall for the Kansas territory summoned a posse, which amounted to some 800 men, most from Missouri, to serve the warrants. The residents of Lawrence, unwilling to put themselves in the position of resisting directly federal authority, offered to permit Donaldson to carry out his duties. On the morning of May 21 one of Donaldson's deputies, with a small party, entered the city, arrested several residents for treason, had lunch at the Free State Hotel, the purported fortress, and returned to the main body of the posse. The marshall's business was complete. At this point, Sheriff S.J. Jones, appointed by the pro-slavery side, stepped forward. He too had warrants to execute. Specifically, he intended to carry out the order to suppress the free soil newspapers and destroy the Free State Hotel. He also needed a posse. The Missourians, led by Senator Atchison, cheered. They would have an opportunity to enter Lawrence after all. Gihon quoted the account of the pro-slavery "Lecompton Union, the most rabid pro-slavery paper in Kansas, the Squatter Sovereign excepted":

During this time appeals were made to Sheriff Jones to save the Aid Society's Hotel. This news reached the company's ears, and was received with one universal cry of `No! no! Blow it up! blow it up!

About this time a banner was seen fluttering in the breeze over the office of The Herald of Freedom. Its color was a blood-red, with a lone star in the centre, and South Carolina above. This banner was placed there by the Carolinians--Messrs. Wrights and a Mr. Cross. The effect was prodigious. One tremendous and long-continued shout burst from the ranks. Thus floated in triumph the banner of South Carolina,--that single white star, so emblematic of her course in the early history of our sectional disturbances. When every southern state stood almost upon the verge of ceding their dearest rights to the north, Carolina stood boldly out, the firm and unwavering advocate of southern institutions.

Thus floated victoriously the first banner of southern rights over the abolition town of Lawrence, unfurled by the noble sons of Carolina, and every whip of its folds seemed a death-stroke to Beecher propagandism and the fanatics of the east. O! that its red folds could have been seen by every southern eye!

Mr. Jones listened to the many entreaties, and finally replied that it was beyond his power to do anything, and gave the occupants so long to remove all private property from it. He ordered two companies into each printing office to destroy the press. Both presses were broken up and thrown into the street, the type thrown in the river, and all the material belonging to each office destroyed. After this was accomplished, and the private property removed from the hotel by the different companies, the cannon were brought in front of the house and directed their destructive blows upon the walls. The building caught on fire, and soon its walls came with a crash to the ground. Thus fell the abolition fortress; and we hope this will teach the Aid Society a good lesson for the future. [At left is an engraving showing the demolished hotel.]

R.H. Wilson, a young Englishman who joined Atchison's forces, recounted the "sack" this way:

So one fine morning we "Border Ruffians," as the enemy called us, struck camp and marched out some fifteen hundred strong, with two 6-pr. field-pieces, to attack Lawrence, my company acting as the advance guard. We halted the first night near Lecompton, our capital, my company being on picket duty, spread out fan-like some two miles round the camp. Next morning Governor Shannon, our own party's governor, paid us a visit of inspection, and was pleased to express his high approval of our discipline and workmanlike appearance.

I can't say much for our discipline myself, but there is no doubt we were a fighting lot, if only the Northerners had given us the chance of proving it.

The morning after the inspection we marched on Lawrence, where we expected a sharp fight, which we were fully confident of winning. My company acted again as the advance guard, and when, about midday, we reached Mount Oread, a strongly fortified position, on which several guns were mounted, covering the approach to the town, great was our surprise to find it had been evacuated. As soon as our general received the report, he ordered our company to make a wide circuit round the town, to seize the fords of the Kansas River and hold the road leading east.

Then he moved the rest of his force to within half a mile of the town, formed square on the open prairie, and sent in a flag of truce, demanding an unconditional surrender of the place. To the no small disgust of the "Border Ruffians," Governor Robinson, without further parley, threw up the sponge, and meekly surrendered the town and the 2,600 men it contained.

No doubt his men were not very keen on fighting, being the riff-raff of the Northern towns enlisted by the Emigrants' Aid Society, and most of them quite unused to bear arms of any kind. Many of them bolted for the Kansas River ford and the Eastern road; and we of Miller's's company took quite three times our own number of these valiant warriors prisoners. I well remember how scared the poor wretches were! I am glad to say that the prisoners' lives were spared, all but two, and they were hanged by the Provost Marshal for horse-stealing, the penalty for which was invariably death, in that Western country, even in ordinary times.

Though the prisoners were spared, I regret to say the town was not, for Atchison's men got completely out of hand, battered down the "Free State Hotel," and sacked most of the houses. It was a terrible scene of orgy, and I was very glad when, about midnight, we of Miller's company were ordered off to Lecompton to report the day's doings to Governor Shannon. There we were kept several days, scouring the country for Free Soilers, and impressing arms, horses, and corn.

[Cutler's History provides a detailed account of the "sack" along with several important primary materials.]

Spasmotic violence continued, most notably the Pottawatomie Creek Massacre led by John Brown in retaliation for the "sack" of Kansas. In May of 1858 the last of the great Kansas bloodlettings, the Marais Des Cynes Massacre, occured. A Baptist minister, B.L. Read, survived to tell the tale.

Sent to Rev. Nathan Brown, editor of the American Baptist. OSAWATOMIE, Lykens Co., Jan. 18, 1859

Dear Brother Brown: . . . Early in April (1858) I moved to Moneka (two miles north of Mound City) with a view to a permanent settlement, intending to devote my entire time to preaching. The friends at Moneka were unable to raise the means for my support, as they expected. I thought best to return to the (Trading) Post, as the people there were very anxious for me to establish a school. I moved back on the 18th of May, with the expectation of opening a school as soon as possible.

I had a piece of ground plowed, which I wanted to put in corn, and the next morning I went to Mr. Nichols to get a horse to mark out the ground for planting. While there a Mr. Taylor came to Nichols' with another man named Allen. Mr. Taylor said that he had come to see me about a school, and I told him what my intentions were in regard to it. A few minutes after Hamilton with about thirty men came up and surrounded us. He ordered me to fall into line.

I said, "No, sir."

He then drew a large revolver and cocked it, and said, "You won't go? G-d D-n you."

I replied that I was willing to do anything that was right. He ordered me to hitch my pony, and pointed to a place to take my stand and I did so. At the same time Taylor and James were taken. Hamilton with a number of his men then went into Mr. Nichols' house, as they said, to search for Nichols. He was absent. They took considerable property from the house, and three horses from his yard. They also took Taylor's, James', and my horses, with the saddles and bridles. They let Mr. Taylor go, keeping four of us as prisoners-- P. Ross, Campbell, James, and myself. Campbell and Ross were taken before I was, with a number of others. All had been let go but Campbell and Ross. A man named Stilwell, driving a team on the road, was stopped and asked where he lived. He said, "Sugar Mound." He was ordered to get out of the wagon and fall into line. He did so. A man was ordered to search me, and I was asked if I had any arms. I told him, no, that I did not carry arms about me. He said, "Haul out what you have got in your pockets." I took out and showed him all I had. He took from me a piece of blank paper folded four double, and about four inches square. After looking at it he commenced tearing it up. I said there was no use in tearing it up, as I generally carried paper for the purpose of making memorands. He said that I should not want it. This, in connection with another circumstance, convinced me that they intended to kill me. I supposed at this time that they had killed Nichols.

They then ordered a march. The men who had charge of Stilwell's team asked what he should do with it. Hamilton said, "Take it along." Presently Captain Hamilton turned to Mr. James and said, "Here, you take this team and take care of it until we call for it. I reckon you would rather go with that than with this crowd." James replied "yes." One of the men said, " There is a d-m good horse," and some of the party replied, "If you like it better than yours, take it." The horse was stripped of its harness and taken.

At the time we were making directly towards Missouri. After traveling about two miles we were halted near Mr. William Hairgrove's house. Here, Mr. Hairgrove was taken from his field planting corn, and brought into line. Mr. Amos Hall was taken from his house and brought in, and also Asa Hairgrove who was at work about his father's house. Starting from this place, we took a northeasterly direction. Soon after starting, Mr. William Colpetzer was brought in and about the same time, Michael Robinson and Charles Snyder were captured. These three were taken from their homes. A wagon was discovered at a distance making towards us and a posse of Hamilton's gang proceeded to see who was coming. It proved to Mr. Austin Hall, and he was brought into the line with the other prisoners. About this time, Captain Hamilton said, "I want to go see my friend Snyder," meaning Eli Snyder. He started with a posse, the prisoners being halted on a high table of land. Soon after we heard the report of firearms. It proved to be Hamilton's attack on Snyder at his house.

Mr. Eli Snyder is a blacksmith by trade and was at work in his shop when they made the attack on him, his brother and a man named Robinson being present at the time. Suspecting foul play, he told his brother to go in the house and get his gun, at the same time taking his own gun to guard him. When the brother got to the house, the posse fired upon Eli, one ball taking effect in the leg and another in the side. Snyder returned the fire and wounded Hamilton and his horse. Mr. Snyder's son was at the house, and fired on the posse, wounding one man and his horse. A part of the main body, which had been guarding the prisoners, left and went to the aid of Hamilton, and soon returned with him.

Captain Hamilton on coming up ordered us to march, and said he would take us down and show us what Snyder had done. After marching us about three fourths of a mile, into a deep, narrow ravine, he ordered us to halt, face front and close up. We did so, and he then ordered his company to come into line about ten or fifteen feet from us, the horses' feet being higher than our heads. He then gave the order to take aim. Doctor H. said: "The men don't obey the order, Captain."

Hamilton gave the order again. Doctor H. said: "They don't all obey." The notorious Brockett turned his horse's tail toward us, and Captain Hamilton said, "G-d d--d you, Brockett, why don't you wheel into line?"

Brockett said he would not have anything to do with "such a G-d D--d piece of business."

Captain Hamilton then ordered his men to fire upon us. We all fell at the first fire. He then ordered some of is men to get off their horses, and go down and see that they were all dead, and if any showed signs of life, to shoot them until they were dead. They fired a number of times. Hamilton said, "There is old Read; he ain't dead." A shot was fired, but missed again. Someone said, "There he is looking at you." A man named Hullard said, "Put the pistol to the ear; shoot into the ear." The man pointed out was Ross, and they fired into him. Some one said, "See what that man," -- meaning Stilwell--"has in his pockets; there is a hundred dollars there." Another said, "There is one that has got a watch."

Soon after Captain Hamilton's company began to move off, and presently I heard my wife speaking to some one. I called three times before she discovered me and came to me. I requested her to go as quickly as possible and get someone to come. She asked me if she shouldn't get some water for us first. I said no, we shall all die. She then left us. My object was to get some one to come and take our testimony, as I did no think that any of us then alive could live long. Mr. Campbell called to me, requesting me, if I should live, to write to his brother-in-law, Mr. Patten, living in Osawatomie, and tell him how he came to his death. As I looked up I saw he was almost dead. I pulled myself to him by the grass and stones, and said a few words to him. I then pulled myself about fifteen or twenty rods into some bushes. I then got up and examined myself, and found that I could walk.

My first thought was to make an effort to find someone to go for a doctor. After traveling about a mile, I came to a house. I stated the facts of the murder to the inmates, and was furnished a horse on which I started, after taking my coat and tying it tight around me to staunch the flow of blood. I traveled about three miles, bearing a little toward home, and then made for the heavy timber about five miles from home. After getting into the timber, I traveled a zig zag course, to prevent being tracked, crossing quite a stream four times. By this time I began to be very faint. I discovered a smoke, and turning to it found one of my neighbors who had fled into the woods for protection. They threw down a quilt and got me on it. I was then about two miles from home. They sent into the settlement intelligence of where I was, and about 11 o'clock at night, my wife arrived. She remained with me until 4 o'clock in the morning, returning about 8 o'clock with two physicians. I was then carried home, and the doctors, after a close examination, thought I might get well.

John Brown and a Massacre in Kansas

William G. Cutler's account from 1883 in his History of the State of Kansas is well-documented. James Townsley, one of the participants, made a public statement of his own role which Cutler reprinted in full. Brown, four of his sons, and several others including Townsley set out to avenge the "sack" of Lawrence. As to the actual killings, Townsley said:

The old man Doyle and his sons were ordered to come out. This order they did not immediately obey, the old man being heard instead to call for his gun. At this moment, Henry Thompson threw into the house some rolls or balls of hay in which during the day wet gunpowder had been mixed, setting fire to them as he threw them in. This stratagem had the desired effect. The old man and his sons came out, and were marched one-quarter of a mile in the road toward Dutch Henry's crossing, where a halt was made. Here old John Brown drew his revolver and shot old man Doyle in the forehead, killing him instantly; and Brown's two youngest sons immediately fell upon the younger Doyles with their short two-edged swords. One of the young Doyles was quickly dispatched; the other, attempting to escape, was pursued a short distance and cut down also. We then went down Mosquito Creek, to the house of Allen Wilkinson. Here, as at the Doyle residence, old John Brown, three sons, and son-in-law, went to the door and ordered Wilkinson out, leaving Frederick Brown, Winer and myself in the road a little distance east of the house. Wilkinson was marched a short distance south and killed by one of the young Browns with his short sword, after which his body was dragged to one side and left lying by the side of the road.

We then crossed the Pottawatomie and went to Dutch Henry's house. Here, as at the other two houses, Frederick Brown, Winer and myself were left outside a short distance from the door, while old man Brown, three sons and son-in-law went into the house and brought out one or two persons with them. After talking with them some time they took them back into the house, and brought out William Sherman, Dutch Henry's brother and marched him down into Pottawatomie Creek, where John Brown's two youngest sons slew him with their short swords, as in the former instances, and left his body lying in the creek.

Historians still argue over Brown's motivations, and over his sanity for that matter. Clearly he was enraged over the "sack" of Lawrence. Cutler noted that there had been rumors of pro-slavery settlers intending to do something of the same sort to the free state people and suggested that Brown's actions were preemptive. Townsley provided a more direct explanation of the attack:

He [John Brown] said it was to sweep the Pottawatomie of all Pro-slavery men living on it. To this end, he desired me to guide the company some five or six miles up to the forks of the creek, into the neighborhood where I lived, and point out to him on the way up, the residences of all the Pro-slavery men, so that on the way down, he might carry out his designs. Horrified at his purpose, I positively refused to comply with his request, saying that I could not take men out of their beds and kill them in that way. Brown said, 'Why, don't you fight your enemies?'

In Kansas the massacre unleased a season of guerilla warfare with each side raiding the other's settlements, stealing livestock, and occasionally killing each other. English adventurer and "ruffian" R.H. Wilson recalls an incident a few days after Pottawatomie:

On the march. . . to Stranger Creek, and whilst scouting ahead of the company with two other men, I came on the bodies of two young men lying close together, both shot through the head. The murdered men, for it was brutal murder and nothing else, were dressed like Yankee mechanics, and apparently had been done to death the previous night.

I had heard that one of our scouting parties had taken some prisoners, but that they had escaped; and now it was plain what had been done by some of our ruffians.

In the North the massacre was downplayed or ignored by Republicans. Mordecai Oliver's Minority Report of the Special House Committee on the troubles in Kansas (the Howard Committee), pp. 105-107, presented clear evidence linking Brown to the murders along with graphic testimony of their brutality. In Kansas, among free state and proslavery partisans both, Brown's involvement was an open secret, as a letter written immediately after the massacre indicates by Edward Bridgman, himself a free soiler and militiaman, makes clear.

Tuesday, [May] 27.

Since I wrote the above the Osawatomie company has returned to O. as news came that we could do nothing immediately, so we returned back. On our way back we heard that 5 men had been killed by Free State men. the men were butchered -- ears cut off and the bodies thrown into the river[.] the murdered men (Proslavery) had thrown out threats and insults, yet the act was barbarous and inhuman whoever committed by[.] we met the men going when we were going up and knew that they were on a secret expedition, yet didn't know what it was. Tomorrow something will be done to arrest them. there were 8 concerned in the act. perhaps they had good motives, some think they had, how that is I dont know. The affairs took place 8 miles from Osawatomie.The War seems to have commenced in real earnest. horses are stolen on all sides whenerver they can be taken. . . .

Weds eve.

Since yesterday I have learned that those men who committed those murders were a party of Browns. one of them was formerly in the wool business in Springfield, John Brown[.].

Nonetheless Brown travelled freely through the North, speaking in public, and raising funds for the free state cause. He always denied that he had been responsible. About a year before his death in 1919 Salmon Brown, who participated in the Massacre, dictated an account of what happened to his daughter. In it he confirmed the key details of Townsley's narrative.

James Buchanan and the LeCompton Constitution: Making a Bad Situation Worse

James Buchanan inherited this crisis when he assumed the presidency in 1857. He pledged in his Inaugural Address to guarantee to every male resident of the territory an opportunity to vote on the question of slavery:

. . . it is the imperative and indispensable duty of the Government of the United States to secure to every resident inhabitant the free and independent expression of his opinion by his vote. This sacred right of each individual must be preserved. That being accomplished, nothing can be fairer than to leave the people of a Territory free from all foreign interference to decide their own destiny for themselves, subject only to the Constitution of the United States.

The whole Territorial question being thus settled upon the principle of popular sovereignty—a principle as ancient as free government itself—everything of a practical nature has been decided. No other question remains for adjustment, because all agree that under the Constitution slavery in the States is beyond the reach of any human power except that of the respective States themselves wherein it exists. May we not, then, hope that the long agitation on this subject is approaching its end, and that the geographical parties [a reference to the Republican Party which had support only in the North] to which it has given birth, so much dreaded by the Father of his Country, will speedily become extinct?

There had been several elections already in Kansas but none meeting the president's criterion. Yet, if such an election could be held, there actually was reason to believe the crisis could be resolved. Buchanan turned to Robert Walker, an experienced politician with whom he had served in the Polk Cabinet. Walker, pictured at left, lived in Mississippi and owned slaves but had grown up in Pennsylvania. He was what Buchanan most needed, a realist not an ideologue. Walker, upon arriving in the territory, immediately counted heads. He wrote to the president: "Supposing the whole number of settlers to be 24,000, the relative numbers would probably be as follows: Free State Democrats, 9,000, Republicans, 8,000, Proslavery Democrats, 6,500, Pro-Slavery Know-Nothings, 500. This meant that there were more than twice as many Free State voters as proslavery (17,000 vs. 7,000) but nearly twice as many Democrats as Republicans (15,500 vs 8,500). A fair and open election would mean Kansas would enter the union as a free state with a substantial Democratic majority. Given the party's overall poor showing in the North in the last two elections, this would be a welcome outcome. The challenge facing Walker was persuading the free state settlers to participate in the upcoming election to choose delegates for a constitutional convention. This he failed to accomplish. Instead the free state side again boycotted. After all, none of the elections overseen by territorial governors appointed by Democratic Presidents had been fair.

There had been several elections already in Kansas but none meeting the president's criterion. Yet, if such an election could be held, there actually was reason to believe the crisis could be resolved. Buchanan turned to Robert Walker, an experienced politician with whom he had served in the Polk Cabinet. Walker, pictured at left, lived in Mississippi and owned slaves but had grown up in Pennsylvania. He was what Buchanan most needed, a realist not an ideologue. Walker, upon arriving in the territory, immediately counted heads. He wrote to the president: "Supposing the whole number of settlers to be 24,000, the relative numbers would probably be as follows: Free State Democrats, 9,000, Republicans, 8,000, Proslavery Democrats, 6,500, Pro-Slavery Know-Nothings, 500. This meant that there were more than twice as many Free State voters as proslavery (17,000 vs. 7,000) but nearly twice as many Democrats as Republicans (15,500 vs 8,500). A fair and open election would mean Kansas would enter the union as a free state with a substantial Democratic majority. Given the party's overall poor showing in the North in the last two elections, this would be a welcome outcome. The challenge facing Walker was persuading the free state settlers to participate in the upcoming election to choose delegates for a constitutional convention. This he failed to accomplish. Instead the free state side again boycotted. After all, none of the elections overseen by territorial governors appointed by Democratic Presidents had been fair.

As a result, the proslavery side won. And they wrote a constitution, known as the LeCompton Constitution. It would have made Kansas a slave state. There was, however, still hope, Walker maintained. Buchanan had pledged that the residents of Kansas could vote on the proposed constitution. Those who drafted the LeCompton Constitution had no intention of allowing an up or down vote. Instead they proposed a referendum limited to the question of slavery. William G. Cutler provided a lucid summary of the choice voters faced:

The slavery clause gave the Legislature power to provide for emancipation (by compensation to the owner) of all slaves; but denied the power to prevent the introduction of more slaves. A vote 'for the Constitution with Slavery,' was a vote to establish and forever maintain the institution, with the power to emancipate vested solely in the Legislature. A vote 'for the Constitution with no slavery,' was a vote to recognize the existence of slavery now there, to keep those slaves now in the Territory, and the natural increase of slaves during their lives, and was a vote to 'strike out' the power of the Legislature to emancipate. The Constitution 'without Slavery,' meant that slavery in the Territory shall be confined to slaves now there, and their increase from generation to generation, with no power on the part of the Legislature to emancipate by compensation, or in any other way. The Constitution 'with Slavery,' allowed more slaves to be brought to Kansas, but gave the Legislature power to provide for their emancipation.

Walker would have none of this, but Buchanan determined that the LeCompton provisions met his criterion for a fair vote on the issue. This decision not only outraged Republicans, it produced a revolt within his own party led by Stephen A. Douglas who saw LeCompton as travesty on his principle of popular sovereignty. Buchanan prevailed in the Senate but not in the House. The House measure which did pass called for a resubmission of the constitution to the voters of Kansas. This failed in the Senate. The bill that finally did pass, the English Bill, offered Kansans a twofold bribe. If they would adopt the LeCompton Constitution with slavery intact, they would be admitted into the Union and receive 5,500,000 acres of public lands for schools and other purposes. If they rejected LeCompton, they could not reapply for statehood until their total population increased to 93,500.

Kansans resoundingly rejected the LeCompton constitution by a six to one margin in August of 1858. Cutler provided a county-by-county breakdown of the vote. Even Atchison, named after the Missouri Senator, voted against it. The struggle over Kansas was finally over. That for the Union was about to begin.